Rattlers

by Melissa Knopp

The first rattlesnake I ever saw was in the bed of my father’s pickup. I was five, maybe six years old. It was an especially hot, dusty summer, the year the water park on Canal shut down and fires jumped the 240, blackening the median. I remember the way the setting sun sparked on the water in our ditch, dogs barking across the street. My brother, Ezra, and his friends had found the snake on the horse trail and brought it home. Mom didn’t want that thing in her house, didn’t want it in her yard either. They decapitated it in the truck bed with a square shovel from the garage. I watched Patrick kick its body from the bed, keeping the head and the rattle. I think someone laughed. One of them took the head home, a trophy. I think my brother still has the rattle somewhere in his new house on the Wet Side.

The next time I saw a rattlesnake was years later, on the road home from soccer practice. It was late August, the summer I got my first pair of glasses and the Mendez family moved in at the end of the cul-de-sac. The snake was flattened and smooth, but we could tell what it had been from the brownish blotches down its back and the bubbly end of its tail. Ezra, a recently licensed driver and my new chauffeur, crouched next to it, flattening his palm on the hot asphalt. I thought he might be crying, but when he looked up his eyebrows were drawn low and his mouth pulled tight over his teeth. His voice was flat, toneless when he said that people didn’t care about animals, that snakes never hurt anyone except to save themselves. His shoulders tensed when I brought up that rattler in the pickup. He told me that was different, that was just fun with the guys. He said he hadn’t wanted to kill it. I told him it seemed a lot of life was just “fun with the guys,” at least when you were a guy. He watched me for a long time before looking back at the road.

I saw a rattlesnake last week, alone in my car, heading home from some party. I wanted to call my brother, to tell him, but I couldn’t. For whatever reason, I thought if he knew I had seen another dead snake, it might kill him. Stupid since he’s a biologist, but I’m sure he still loves them, feels the loss more acutely than anyone else. I wonder if he thinks about that first rattler the way I do— an innocent, a casualty of his adolescence. He seems so different now, gentle and kind and clever. I never brought it up again, and he didn’t either, but I knew he’d be sad to know I’d never seen one alive. Not many people do. You’re not supposed to see them, unless you’re about to step on one. That’s when they rattle, let you know where they are, but it’s often too late, and then you’ve been bitten. It’s self-defense, but somehow, you’ve become the victim.

This snake was a hit and run. Typical in this area, like tumbleweeds and stucco houses and drive-through coffee kiosks. Night blindness made me squint, but I pulled over as soon as I realized what I had seen. I parked on the gravel shoulder, leaving my keys in the ignition and the door open. Not a lot of traffic on Reata at night. I could hear an owl singing, cars moving on the highway nearby. It had been a hot day, tar bubbles popping under my shoes as I walked. I crouched on the pavement. He had likely come out of the sagebrush to sun himself, and now here we were. He looked like a dirty old shoelace twisted across the blacktop. I couldn’t stop staring. I thought I might cry as I sat, putting my arms around my shaking legs.

Born and raised in Kennewick, Washington, Melissa Knopp is the youngest of seven children. Her writing is deeply rooted in Eastern Washington life, as well as the interesting dynamics that result from being part of a large family. Through her experiences, she hopes to bring new flavors of the PNW, as well as France and Southern California, to her work and her audience. Melissa is currently pursuing an undergraduate degree in Creative Writing at La Sierra University.

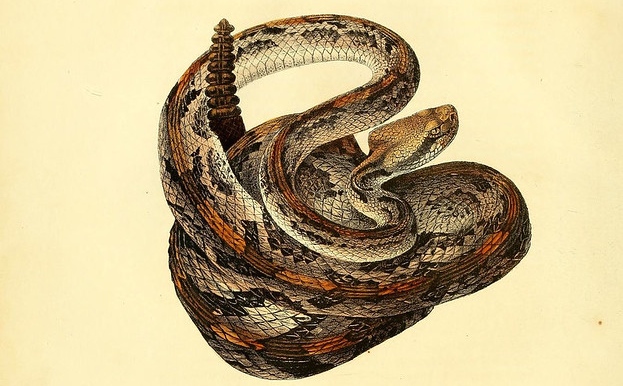

Image: North American herpetology. v.2. Philadelphia :J. Dobson,1836-1840. biodiversitylibrary.org/page/35765728

.