Hook and Eye

by Megan Baffoe

Ella waded out into the river the night before the wedding.

I fetched her in, at perhaps two-o-clock, pale as her nightdress and near-drowned by the rain. She cried like a newborn as I ran the bath and like a widow as she drank her tea. “He’s waiting for me,” she kept saying, “he’s waiting for me.” So I pulled open the curtains.

“He can see you in here,” I repeated over and over until she had fallen asleep. “He can see you in here.”

*

June and Her Betrothed were married the next day, beneath a pink-and-yellow-sky. She was swan-like in her gown, all whipped-cream white skirts and exposed neck. Her hair was gone, so her neck was all you could see—white and waxy like a slab of cheese. When I blinked, I could see phantom bruises, marking the pale skin; they disappeared when I concentrated on the vows.

I can hardly be blamed for my lack of attention. It had been months since we had seen her; and then she was here, stepping out of a cherry-red car with no tights on and curls cropped to her scalp like a boy’s, and a man in the driver’s seat. I watch them now, laughing on the lawn; can see Father striding in on the scene, hunter’s gun in hand. (Have been seeing him more often, lately.)

He disappears once I attend properly to the vegetables.

I prepare the meals alone; Ella cannot stand the kitchen. She hates the hooks; Father used to hang his game from them, and she would insist that she could see the dead things squirming. She’s always had an active imagination—her darling, she tells me, enjoyed June’s wedding very much.

It’s a nicer story than what I am left with—which is, a pile of red onions, and one sister married and the other mad.

*

They come in once the dark begins to settle.

The Betrothed doesn’t look at June. Rather, his gaze is on the woodwork, ornate as it is rotting, the fading velvet of the curtains, the cracks in the best china. He even has the nerve to grin at me, although he must know by now that I will not return it.

What are you smiling at? my father’s voice barks. But a woman’s mouth is her mother’s.

So I say, “I hope you like vegetable soup.”

June says he does. I know by her eyes he doesn’t. I’m more interested in her cheeks; pale, under the artificial blush. And he starts talking more, then, an unraveling thread of food budgets and new countertops and professional help, and I realize that he has decided to stay. Here, of all places, with his wife’s unwed sisters. In a rotting house full of ghosts.

He keeps talking, but I don’t listen. I’m thinking about my father’s dead rabbits, and the Betrothed’s new car and nice watch, and what, as poverty does not confine him, could possibly keep him here.

I find out the very next night.

Ella is Ella. Painting-like, in her nightgown, staring through her arched window as if she can see Heaven there. The window is open; her palms are pink with the cold and spread to the dark air; she is mumbling, a stream of consciousness shuddering back and forth across the night’s silence, but I can’t make out the words.

They are private. I shut the door, and ask him what he is doing. He chuckles, nervously, as if he has been posed an awkward question at a dinner party and not caught lurking outside my little sister’s door.

“I heard her talking. It woke me up.” Liar. “Is she okay? June did mention that she wasn’t quite—right.”

“She’ll be fine,” I say, hopefully coldly enough that he mentions it to June. “This is routine for her. I’ll check on her again in another hour, and then get her settled and into bed.”

He nods, face sheepish, but I can see the cold rage behind the mask now that I know what kind of monster he is. I wonder if he thinks about Ella’s hair, long and falling down her back.

He stops before June’s door. Asks me who she is talking to.

My lips purse. He’ll never understand Ella, no matter how hard he tries, even if he has somehow got the measure of June. I resent the question, although I give the answer.

“The moon.”

*

“The moon loves me honestly, and beautifully, and he is never away,” Ella told me. “So I can be loved, even if I am quite alone.” I told her, that I could love her—”but you are a sister,” she told me earnestly, “and cannot love me like the moon loves me.” I left it; I have long resigned myself to making do with the affections I have, but if she cannot, this is the best way. She ignores the boy who looks at her at Church, the man who gives her an extra smile at the market; because she knows we are warped creatures, half-dead things, bathed in boiled water for disease-ridden thoughts and given purple cheeks for red lipstick. June was always going to return home with a degenerate; she wouldn’t know how to find anything else.

It is simply that the silly thing doesn’t know it.

So I sigh, put on my father’s hunting jacket.

My mouth is my mother’s for sure, but I inherited his aim.

Megan Baffoe is an emerging freelance writer currently pursuing English Language and Literature at Oxford University. She is interested in food, family, and fairytale, and keeps track of her published work at http://meganspublished.tumblr.com.

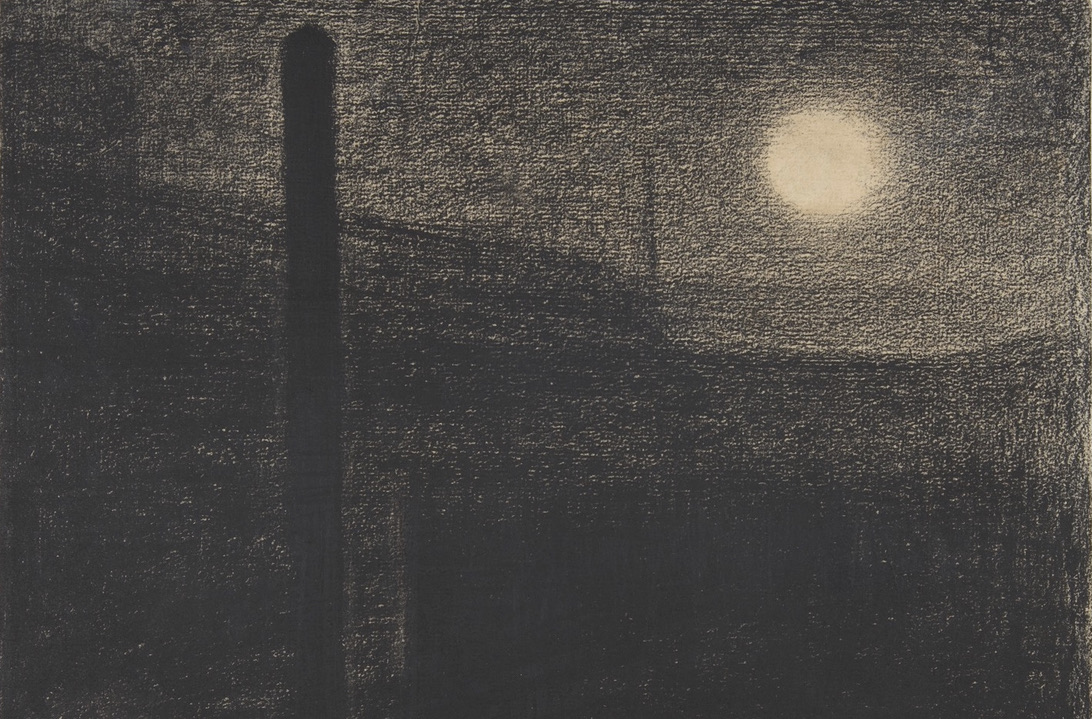

Image: Courbevoie: Factories by Moonlight by Georges Seurat (French, Paris 1859–1891 Paris), MET, Gift of Alexander and Gregoire Tarnopol, 1976.