← Issue 10

Phase Change

by Virginia Laurie

The clouds broke, and just like that it was over: apocalypse rendered as a simple sunset, a calm rapture for the last day on earth. She could look outside her window to see the dying of the light and leftover jet fuel, still curling behind the roofs where the rocket’s tail had been, moving like incense, or a snake in low grass with the skyscrapers as blades. It wasn’t scary though, just hauntingly beautiful, she thought, as the light continued to die. Everywhere, the energy trapped in the water exploded until each river ran rainbow, and the ducks coated themselves in too much holographic sheen to swallow.

It wasn’t ugly, though. They choked with a grace she admired as her son prodded her own throat questioningly. It was nice of them, she thought, to put little windows in the bunker. It was nice to get some time off work, finally. When the sun imploded, the yolk ran towards each corner of the page.

She prayed the next planet would be kind to the Explorers, or they kinder to it. She briefly wondered what it would be like to live in Phase 3.0 with her husband and the eleven others (a pediatrician, one surgeon, an army medic, two marshals, four scientists, a president and a poet) entering orbit now. A single lifeboat, and it had already left. There were no children on the rocket, but there were thousands of frozen eggs.

She held her son in her arms, and together, they ogled the crushing orange of everything coming to claim their molecules. She wanted to smile, or laugh, or to do anything at all with her mouth, but there was simply too much rainbow to swallow. If she had more Before time, she might’ve looked up the size of a human child’s heart and found the formula to predict it. It wouldn’t have mattered any more or any less than anything else, but it was all she could think about Now. Not the digits themselves, but the ability to quantify.

Her husband was outside the stratosphere because he could quantify anything. She was down here because an advanced degree in linguistics wasn’t enough to involve her in the process of civilization-building. It’s not that she’d really thought she was one of the twelve most essential people on the planet, but doesn’t everyone to some extent? She knew she wasn’t special, but it still stung a bit, like the 10+ UV that had been burning their faces for weeks now.

Her son’s cheeks were chapped and cherried against her shivering chest. She thought, How big is his heart by now? How safe could it be, if the sun could implode? It was like the time they’d taken him to her mother-in-law’s lake house, and he took his fawnlike and stuttering feet too close to the edge of the dock. She’d thought she’d known fear then, the real stomach-dropping kind. Now, she looked out the window and saw her ultrasound.

Love had made her universe so small.

Everything that mattered clung to her neck, but somewhere up there, higher than comprehension, she knew a picture of them all Before, happy and smiling their healthily rosy cheeks, sat tucked inside her husband’s shirt pocket. She knew because she’d put it there that morning after pressing it. No one would see it under the space suit, but she would know, and he would. When the time had come to say goodbye, she’d had no words. She’d tried to sum it all up by tying his tie. She’d patted the pocket above his chest sloppily and wet the corner of his neck. She still hadn’t spoken since the night before when he’d bent down to take the plastic truck from her son’s hands and tell him about the big business trip.

She imagined the way the edges of the photo might fray from repeated handling. They wouldn’t be forgotten yet, at least. Her love would outlive her. As she touched the glass, her son did the same, and he watched her face, which must’ve been aglow from the fire, like it was his backup sun. If that was true, she’d stand there forever, holding him closer and closer until she could finally intuit the size of his heart (A whole mango? A clementine?).

His small face was so very close to her own and the outside world’s rending, and the sound of metal tearing suddenly rose in a great wave one every side. Her eyes slid to the window, the decreation she could start to feel. As her son mimicked her actions once more, they became complete equals for the very first time. They were their own world, and their last one. She realized she had one smile left, so she gave it to him. Her son returned the grin as fire filled everything.

Virginia Laurie is an English major at Washington and Lee University whose work has been featured in Apricity Magazine, South Florida Poetry Journal, Phantom Kangaroo, Cathexis Northwest Press and more. https://virginialaurie.com/

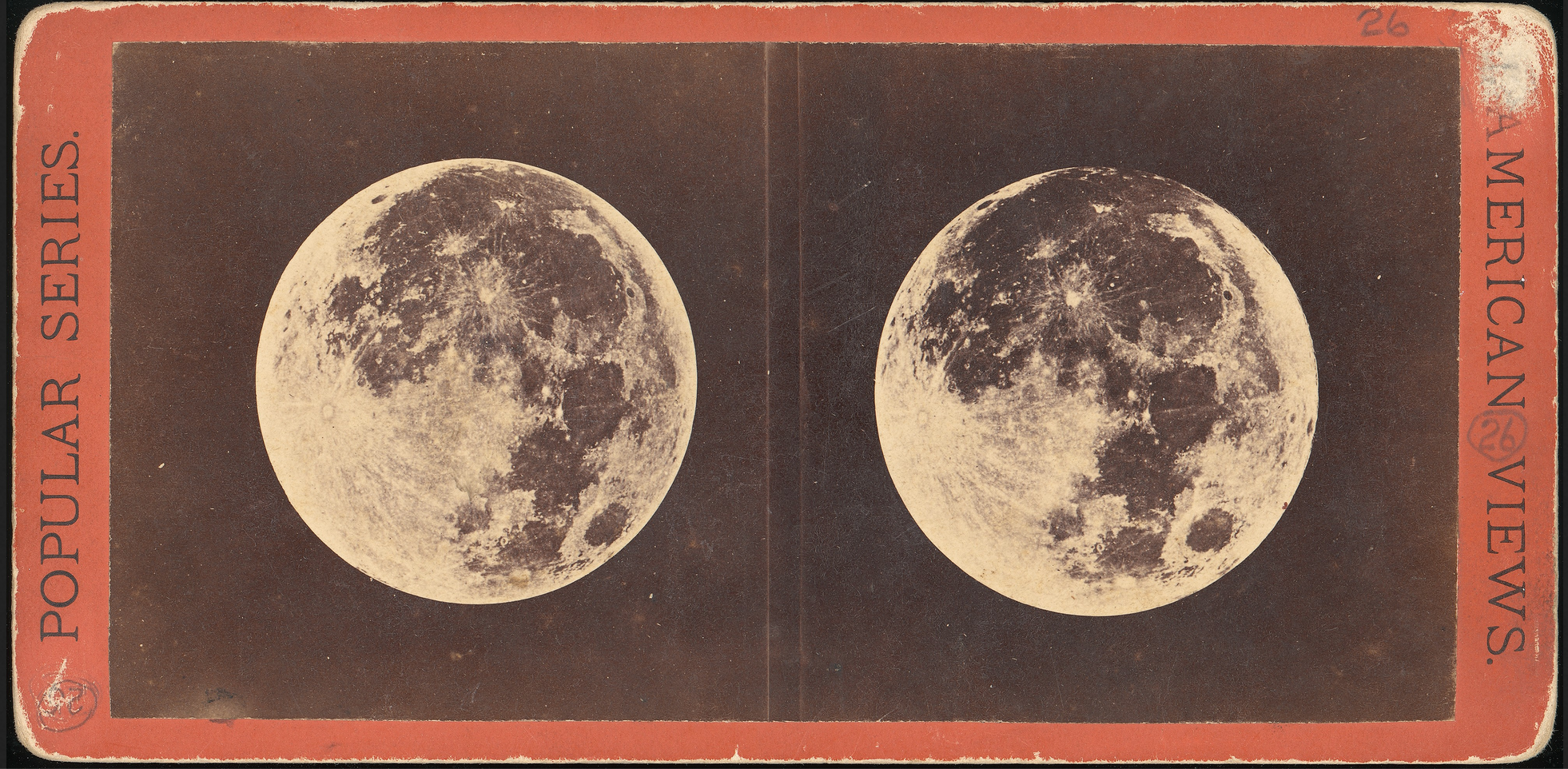

Image: Sunset Sky by John Frederick Kensett (American, Cheshire, Connecticut 1816–1872 New York). Date: 1872. MET