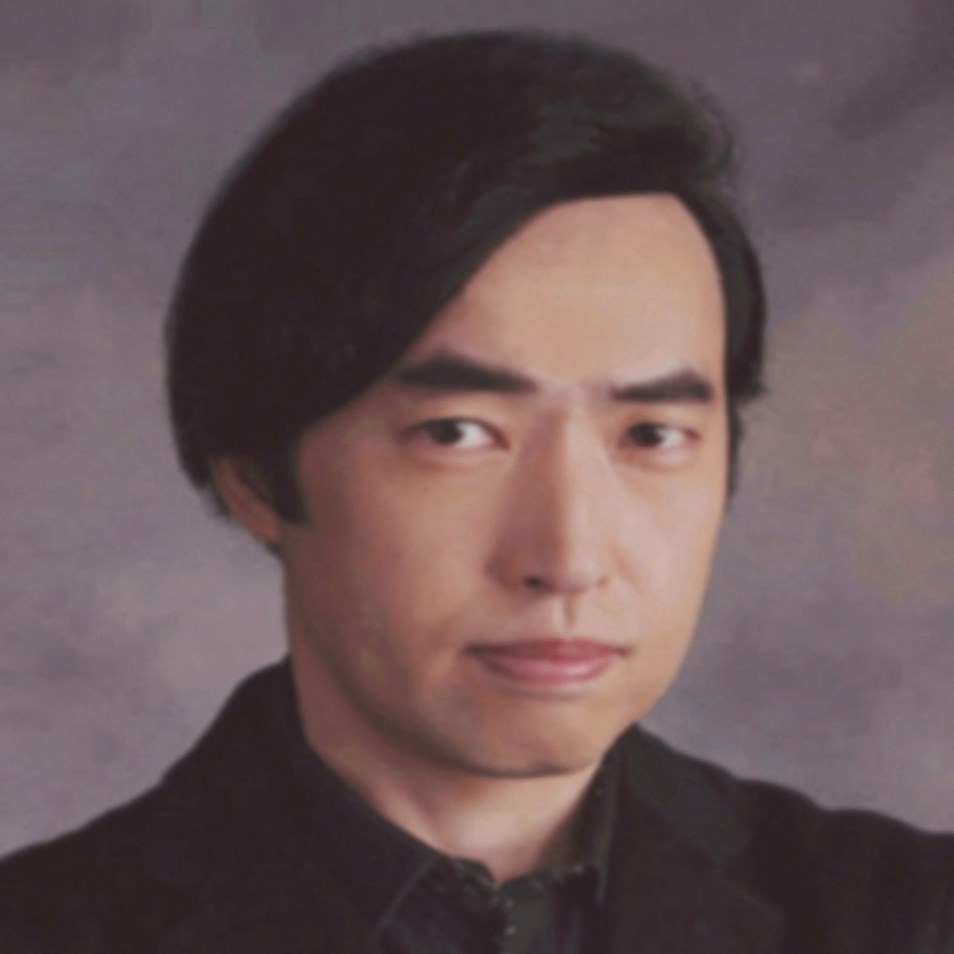

Interview with Ryota Matsumoto, Artist for our ISSUE 4 Cover

Ryota Matsumoto talks with Ashli-Jane Benggon about art, his inspiration, and architecture.

Can you tell me about the inspiration behind your art piece, “Still from Cities Inextricable Velocities”?

The new landscape of the post-industrial city has emerged with a socio-cultural milieu that is characterized by de-centralized, stratified and destabilized spatial cartography and controlled under the post-Fordism algorithmic hegemony. In our collective consciousness, the pathogenetic substrate of the urban apparatus is where the individual has been embedded psychologically and correlates with the mesh work of neuro-economical abstraction, experiencing debilitating alienation and psychosomatic dislocation. The regime of neuro-capitalism disintegrates the preceding modalities of social collectivity in favor of network-based immaterial connectivity. It depersonalizes urban dwellers in favor of the sensorial data of neural subsumption and the digital economy.

Tell me about your history and relationship with art.

I studied both painting and art history before embarking on my career as an architect, so I have a longstanding interest in how the two fields have evolved and interacted with one another in the process of cultural production over the last few centuries.

There used to be a symbiotic relation between architecture, art and science: the reciprocal influence as well as the mutual encapsulation between these fields often culminated in creative achievement and contributed to some highly innovative moments in time, especially from the Renaissance to the late pre-Industrial age.

The segmentation of creative fields only occurs during the process of industrialization, which favors the division of labor as the nebulous concept of professionalism in the early 19th century. Evidently, RIBA separated architecture from the field of art as a professional field in the 1950s, and that drove a wedge between two fields in Britain. The academic trend of disciplinary fractalization disseminated in the rest of the world during the same period.

As for the post-industrialist society, artists and architects share and embrace the same graphics software and emerging technologies. These include 3D printing, parametric scripting and bioinformatics optimization in the discursive framework of today’s capitalist society platform. As spatial practitioners, we need to return to dual roles in order to further deterritorialization and to decode cultural production in this age.

How has studying architecture influenced your art?

There is an axiomatic system embedded within design-oriented practices that are hinged on a set of isomorphic semiology or an algorithmic process that is catered to consumer culture and the digital economy. My education and professional practice as an urban planner and architect led me to reconfigure and reevaluate my cognitive perception towards art by embracing design-oriented semiotics as my primary modus operandi. I perceive art objects as continuously decoded assemblages or epiphenomena arising from ever-evolving confluences of semiotics, phenomenology and transcultural sensorium.

Are there any artists you admire and/or take inspiration from?

I admire a number of post-serialist electroacoustic composers, notably Jani Christou and Roland Kayn. I also take inspiration from both the compositional and architectural work of Iannis Xenakis, who influenced both of the aforementioned artists to a considerable degree. Xenakis organizes his music based on underlying statistical formulae, translating the architectural spatiality into clusters of microgranular tonality.

I think that the potential of microtonal indeterminacy, such as the stochastic synthesis of tonal grains, is an area of interest in the field of spatial exploration that has yet to be examined in both architectural and art practice. Instead, people have been more focused on the current semiotic agency of the artistic realm, which is more aligned with serialism or repetitive notations in terms of compositional methodology.

What is your favorite medium to work with?

I always love to work with acrylic and ink. My design-related practice revolves around digital media, but I am more at ease with traditional approaches. Our spatial notion of cognitive mapping shifted abruptly in 1989, when the first wave of digital optimization emerged and replaced previously dominant analog-based conjectural processes. I was educated as a designer around the period of this paradigm shift, which is one of the reasons why I incorporate hybrid media for art-oriented projects. Essentially, hybrid media is conceived as a multimodal approach for articulating and redefining the manifolds of topological space that continue to transform metaphorically in the context of the space-time continuum. In short, the morphological transduction of architectural space through multi-layered media facilitates the perpetual modulation of allagmatic operations in order to attain the continued transformation of metastability.

Do you have any advice for younger or aspiring artists?

We need to transcend the de facto dichotomy of empiricism and rationalism that is immanent in embedded and embodied entities. Hybrid media is one trajectory to make a rapture for becoming or to draw a line of flight that breaks the mold of the preconceived hylomorphic notion of existentialism, but there are still uncharted territories and new areas for creative exploration, particularly in terms of the affect-driven epistemology of perception.

This interview was conducted by Ashli-Jane Benggon, the nonfiction editor at The Roadrunner Review.