Astronaut

by Navami Shenoy

I craned over my sketchbook, my mother walked into the room and spoke some words—instructions to turn off the stove if the rice was cooked before she returned home. But at that moment, for all I knew, she could have been talking about rabbits cartwheeling in the garden because my mind was brooding over a life-and-death problem: What should I take for tomorrow’s school lunch?

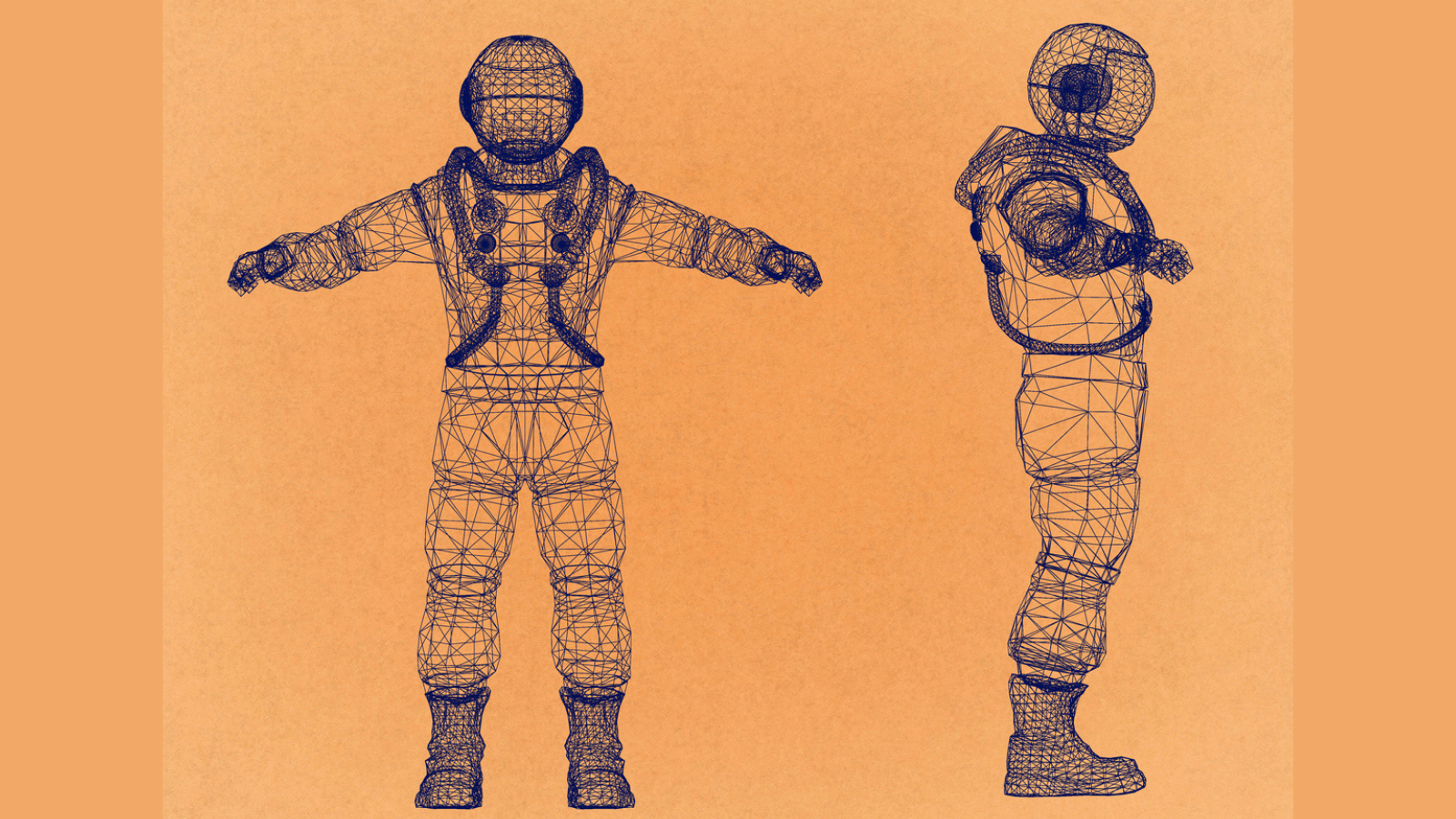

In my sketchbook, a graphite astronaut watched a graphite seedling sprout on an unknown planet—or was it the last sapling on a forlorn Earth? I imagined the sapling quiver as the astronaut reached out to pluck him away.

But this is our home, the sapling said.

“No more,” the astronaut replied.

As I sketched its curious, little leaves, the sapling murmured, Where is home, then?

The question flash forwarded two years into the future and knocked on the window of my plane to Chicago. The Italian man next to me repeated himself for the third time as I struggled to hear him over the drone of the engine. “So where are you from? Where is your home?”

I twirled my glass of orange juice while I thought of a possible answer. Should I say Delhi? But I had just moved there. Should I say Noida, the place where I was born but have not seen since, or Kanpur, the town still recovering from my childhood mischief? Or should I say Mangaluru, a city I hated for its incessant rains but was the place where I made lasting connections, where all of my friends remain?

My father’s company relocated him every three years. They had a quirky management style. Employees who requested to go to Mumbai were moved to the other side of the country. Demand too much and find yourselves in a middle-of-nowhere town with one electric pole and two stop signs. My father, however, would say, “Just throw me anywhere,” and they granted his wish. It didn’t bother him much; he was a traveler at heart, and besides, he considered our ancestral house in the small town of Shimoga as his real home. He grew up among its old red walls, low ceilings, and small windows, as did my grandfather before him.

I visit Shimoga maybe once a year and associate it with the pain of slow WiFi. I criticize my grandparents because their footsteps never fall far from that house. I beg them to come live with us, but they stay stubbornly planted as if they were trees and their roots and the floor were one.

As I debated painting the astronaut in white, my thoughts churned. Nine different houses flashed before my eyes. Countless faces, packed boxes, and school uniforms zoomed past like a train. In came the struggle to transition into a new school and catch up with the curriculum, and out went friendships, time, and money. I dropped the pale paint tube; the bleakness of such memories made me so dizzy I wanted to see no more of that color.

Over time, I noticed that each school had its own culture, its own etiquette. The sooner I identified it and adapted, the easier it was to mingle with students and keep up in class. But there was never enough time for bonding. I was inside an endless video game that I kept losing, having to start over each time. Until I found a way to win.

My mother showed me how without knowing it. There were two things she loved: cooking and plants. Wherever we lived, she grew a garden. Each house smelled of roses, basil, jade, and hibiscus. Each time we moved, it would break her heart, but she would give these plants away to another gardener.

At our new home, she would pluck a basil leaf and place it on the curry, working her magic into the lunchbox I took to school. I discovered that food was the best way to win people’s hearts. At lunchtime the cultural diversity of India would shine. I would lay open my lunchbox and say, “Who wants some paneer?” The entire classroom would attack my food. In return, I got a bit of everyone’s. The Tamilians brought their rice cakes, the Gujaratis their khakhra. There were those who stared at their desks because they couldn’t afford lunch every day, and those who brought Turkish Delight from Istanbul for dessert. Food brought us together. In every school I went to, I started the tradition of sharing food, making memories that lasted. The plants my mother grew still refresh the air of someone’s home, and the food she made has become a cherished classroom memory.

My mother returned home just as I finished painting the astronaut. The air smelled of burnt rice, an awaited scolding, and some ominous news. “The transfer is inevitable,” said my father. I dropped my reverie and tuned into their conversation. Everything stood still. Even the wind chime in the hallway stopped its jingling and stooped to listen.

“Tell them how hard it is to find a decent place to rent in Delhi.” My mother had had enough. She wouldn’t give up her plants again.

“The branch needs me. It’s going haywire without a manager.”

“Those people ask for a monstrous price for a ramshackle hut. Do I smell burned rice?”

The conversation went on for a while. Finally, my father buckled. “We can try to put off the transfer.”

Utensils clinked in the kitchen.

“And she says she wants to go to America?”

No answer. I knew what that meant. Delhi was far away. Moving everything from Mangaluru to Delhi would drain so much money that unless I got a lot of scholarships, we wouldn’t be able to afford something like an astronomical tuition. I could see the hand of bureaucracy reach down and pluck us out of one home and drop us into yet another.

Food was served. We had ramen instead of rice stew, which was fine by me since I didn’t like rice.

Over time, it has become harder to answer the question of home. Each place had a part of me. To ask where I am from implies a fixed home and a sense of permanence. But the laws of physics prevent me from gaining such permanence—I would have to go to a different universe for that.

The universe. So vast, so beautiful. Yet this planet is as far as we can go. If anything happens to our home then, Where would we go? Where would the astronaut take the seedling?

By the time I packed my things for the plane to Chicago, I had decided I was destined to be a nomad. However, I would like to have more control over where I go and why. I would like to see most of the Earth as long as it lasts. Home is where one is at a particular instant of time; I belong everywhere, a citizen of the universe.

I took a long look at my sketchbook. The astronaut and the sapling stood face to face, orange and green, under a dusty pink sky. Each time, there is something to take and so much to leave behind. I decided to leave my sketchbook here. The sapling should be left, so the astronaut can return to get it.

Navami Shenoy is an undergraduate student from India majoring in neuroscience at Ohio Wesleyan University. She sees writing as a way to bring order to the chaos of a wandering mind. Her influences are Markus Zusak, Isaac Asimov, Ovid, and the Brontë sisters. She would like to pursue fiction, nonfiction, or science writing as a career.

The Roadrunner Review nominated “Astronaut” for a 2022 Pushcart Award.